Being a Writer, part 1 of 3

“I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life.”

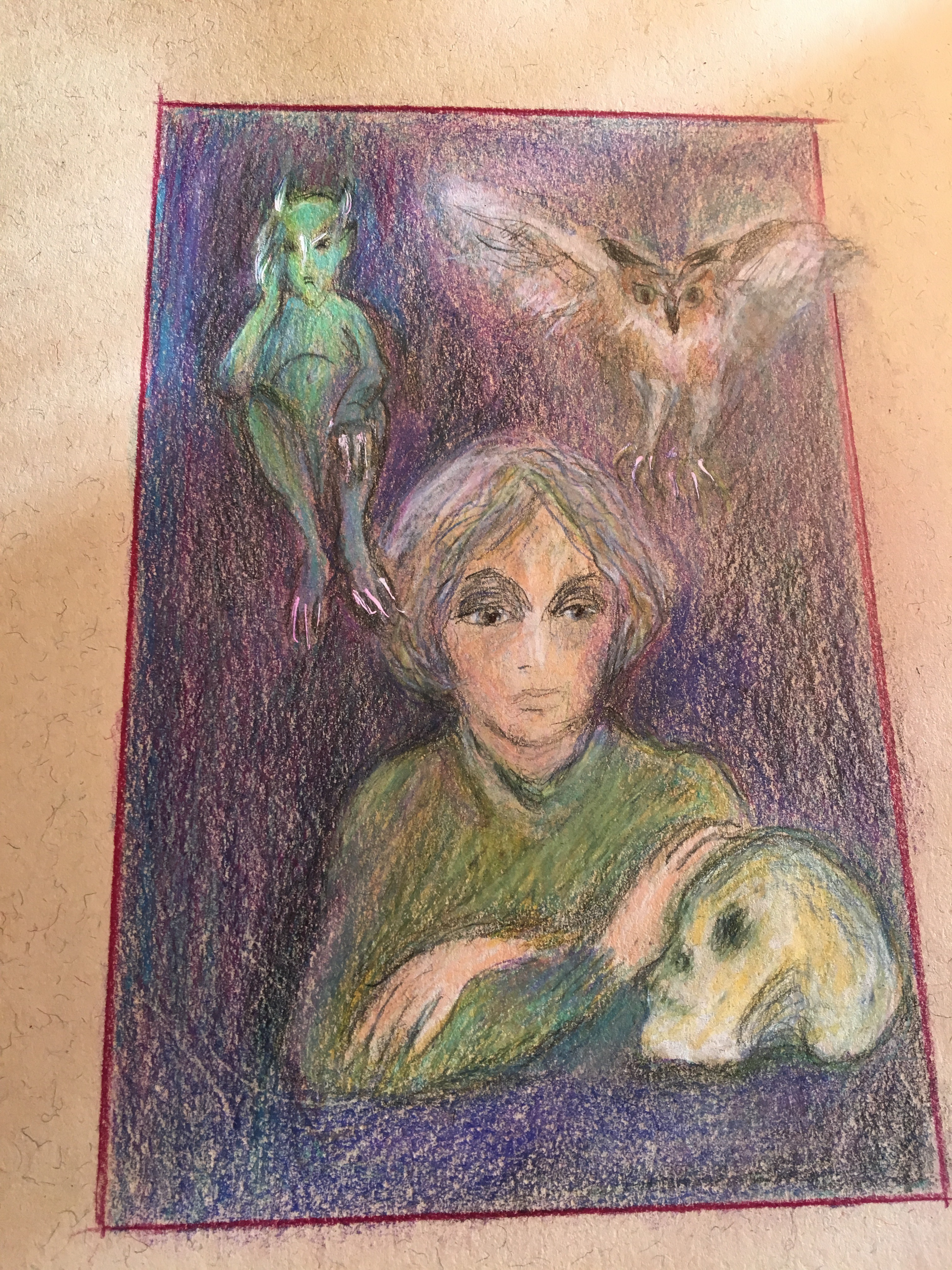

This is George Orwell speaking with his trademark candor in his essay “Why I Write,” which is my gold standard for that topic. All the above could apply to me: the grudging little green demon of feeling undervalued, the owl-shriek and flexing of my talons as I swoop down to get my own back, and, most importantly, the ability to face unpleasant facts.

Last Tuesday I was awoken by a phone call from someone from a revered organization in whose volumes I have felt proud to be listed for the past thirty years. She told me her organization was going to give me a “lifetime achievement award.” All I had to do was answer a few questions. “This isn’t some kind of pitch for money, is it?” I asked, and she assured me it was not. I had been chosen for a lifetime achievement award. So, what were the questions?

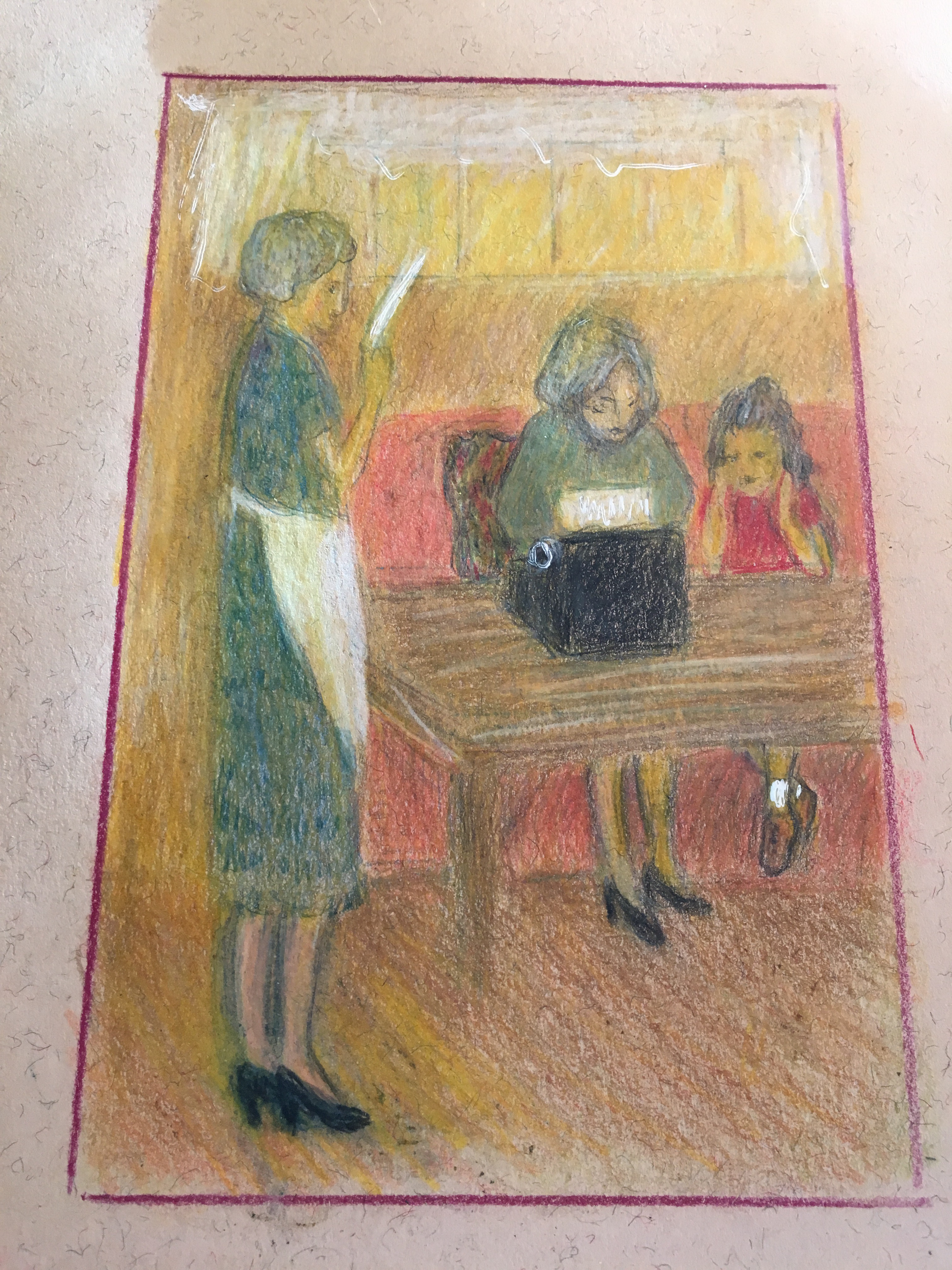

The first was, did I remember what, exactly, made me become a writer, and I said, as a matter if fact I remembered the morning when, at six, I knew this was what I would be. (I had just finished making a drawing of that morning for my next blog.) I described the morning: my young mother typing a love story in the sunny morning room, me sitting close to her on the orange sofa, and my grandmother, standing close by, reading the latest page as it came out of the machine. My grandmother was the first reader/editor and she would say things like, “Kathleen, it’s not clear why the girl turned this man down.”

I went on at leisure because my listener on the telephone was dead quiet. And when I finished my story she made some rather generic comment about “early family influences being important.” Then we went on to some more questions.

At last she said we were ready for the next step. The organization would send me a form and I would write down what I had just said, and then it would be edited and go on their world wide web site. There would be a once in a lifetime cost to me of $200…

“Oh, my dear,” I said, “We have wasted all this time, this is not good.” And I hung up.

I like to think of that young woman–she sounded young and well-trained in her pitch–getting up from her desk and going to the Ladies Room, freshening herself at the mirror, looking into her eyes and thinking, what?

i’d like it if she thought, “Well, my pitch wasn’t completely above board. What should I have done differently? Maybe mentioned the $200 up front? But it says here to read directly from my sheet.” Or, maybe if she is really exceptional, she might go so far as to think: “Am I proud to be working for this organization? Maybe I should…”

It is so hard to tell the truth. It is hard to write the truth. It is hard, even if you are a writer who has the power to “face unpleasant facts,” to stay on track of the nasties and not veer off course to clean them up a bit. I love Orwell because he wasn’t a veer-er. I am trying harder than ever, as I enter my eighth decade, not ever to be a veer-er. The writers I continue to love and admire are not veer-ers.

In my childhood, there was a cartoon in a magazine we got. It was called “The Watch Bird.” Each month there was a failing to be wary of. Did you gossip? Did you shirk? Were you envious?

Then as a warning for next month, there was a final bird looking out at you: This is a Watch Bird watching YOU!”

Have you been a veer-er this month? This is a Watch Bird watching YOU!